Picking up an object is simple, but it's not simple to explain, scientifically.

Popular views from history, which I will refer to as the traditional view, use assumptions.

Assumptions that this alternative view looks to challenge.

Not all traditional views are the same.

But each perspective grouped in traditional view leads to at least one unsolvable mystery.

This article was inspired by Julia Blau and Jeffrey Wagman in their book: Introduction to Ecological Psychology: A Lawful Approach to Perceiving, Acting, and Cognizing.

Existence

Can we assume our perception of the world actually matches the real world?

Descartes (1637) suggested introspection, questioning one's beliefs, was an answer.

An object's existence is based on information gained from our senses.

Thus, we must trust our senses.

But what if we doubt the source, in this case, senses?

Descartes famous phrase "cogito ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am) reflects his reasoning.

“He was not saying that the act of thinking is what made him exist but rather that as he sat there doubting everything, the only thing he could be sure of was that the doubt was coming from somewhere.”

Move forward to the present day and this doubt still holds true.

We know more about how the body and senses work, but our 'sense', our ‘awareness’ of the world comes from (or through) our nervous system.

Our sense organs and brain.

Following Descartes logic, we exist (realism) or we don't (solipsism).

And this is where philosophy gets interesting.

To progress in our understanding, we need to make assumptions.

Assumptions as belief in a truth without proof.

Sometimes we accept the assumption because the evidence cannot be had.

Like with realism or solipsism.

Or...

The assumption has been held true, explicitly, or implicitly, for so long, undoing it would require extensive changes to previous thinking.

Those are the assumptions that separate the traditional approach from the ecological approach.

Knowledge

If we assume the world exists, we need to work out how we gain knowledge.

Epistemology is a branch of philosophy that explores theories of knowledge, with plenty of theories to discuss.

But most agree knowledge comes from experience, which holds 2 principles:

We begin with no knowledge - tabula rasa.

Knowledge is gained from sensory experiences.

Descartes questioned if our senses were true.

If we do the same.

“does our understanding of the world inside our heads correspond with the world outside our heads?”

Either our senses resemble the actual world, or they don't.

But we have no meaningful way to know.

Just like with realism v solipsism, we cannot know which is true.

Thus, we assume our senses (somehow) inform us about the world.

However, explaining the how, is where the science has some wiggle room.

Causes

“traditional approaches - and most modern science - assume local causality.”

Thing A can cause thing B, if A is in direct contact with thing B.

But that isn't always accurate.

We might not be in contact with an object until we pick it up.

Yet we know it exists, the entire time.

This is the action-at-a-distance-problem.

A popular solution suggests there is indirect contact between us and the object.

There is something in-between.

Being philosophical, there are many suggestions, but they all converge to a copy.

A copy of the world that goes between us and the object.

Copy of the world

But now I have questions.

First, how does the copy get into our head?

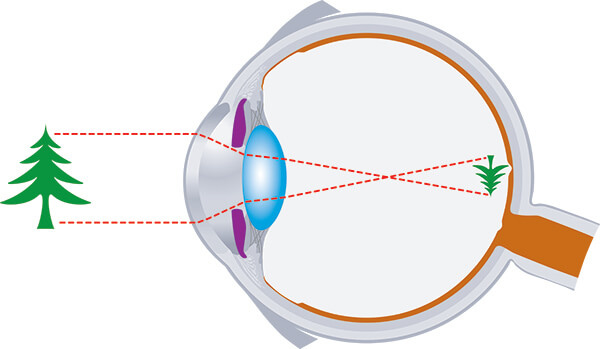

We know light travels in straight lines.

And we have light receptive cells in our eyes.

So light goes from a source to our eyes, hitting surfaces as it travels.

But as you may remember from science at school, the retinal image is reversed.

So our copy of the world is reflected upside-down, reversed, and is two-dimensional.

Not quite what we experience.

Which leads to a couple more questions:

How does the image accurately resemble our experience?

How does the image inform us of the real world?

These questions can lead us to assume the copy is bad.

The retinal image doesn't have enough information.

In other words, the image is impoverished.

We can't see size or distance in a 2D image... on its own.

In the top image, A, B, C, and D will all look the same despite the distance difference.

In the bottom image, A, B, C and D again look the same despite distance and size differences.

However, Helmholtz's theory suggests we infer information, like size or depth, from cues.

We learn cues and abstracted rules through experience, which we use with the image.

This all being done unconsciously.

Rules like:

The farther away an object, the higher up the base looks compared to others.

The closer the object, the lower up the base looks compared to others.

Closer objects block objects farther away.

Which could be illustrated like this:

“Cue + rule + unconscious inference = understanding”

However, multiple circumstances could appear the same, such as:

A sphere, looking like a circle.

1 side of a cone, looking like a circle.

1 side of a cylinder, looking like a circle.

So Helmholtz's proposed the principle of maximum likelihood.

We use the most likely answer.

Modern versions look at probabilities.

The idea is, when combining unconscious inference and the principle of maximum likelihood, we get our mental representation of the world.

A cleaned-up image.

An important point to make here is that the organism is separate from the environment.

Thus, we don't have access to the world, only our mental representation of it.

Unsolvable mysteries

So before we behave, we:

Use our senses.

Make a copy of the world.

We fix the bad copy of the world.

We extract cues.

Apply rules.

Compute likelihoods.

But all that thinking, or those computations, must be performed by something.

The most common name for this, is the central executive.

However, there are a few problems.

Outness Problems

As the central executive is sealed off from the world. And the cells in our eyes, ears, and skin are in here, part of us.

How does the central executive know the stimulation came from out there in the world if it uses our senses as a source?

This is the outness problem.

Source trust problem

If we overlook the assumption, we start with no knowledge.

We can say our senses inform us of the world, so the source must be out there.

But thinking back to the assumption of a bad, or impoverished, image.

Why would the central executive question the accuracy of our senses if it knows no different?

What tells the central executive the world is actually 3-dimensional if we see it in 2 dimensions?

Intelligence problem

In order to use cues and rules, we must make a comparison to past representations.

But where did the previous representations come from if we start with no knowledge?

“Berkeley (1709) suggested that we did not need to give any special information to the central executive as long as the organism has at least one sense that does not need to be interpreted.”

Which doesn't work.

Berkeley suggested touch as a sense that doesn’t require interpretation.

But we can see, hear, smell something we haven't touched, and still know what it is.

In addition, assuming the central executive has an accurate representation (somehow), how does it know what properties matter?

Is the keyboard property, part of the computer representation? Is the mouse? The screen?

How do we gain knowledge about something for the first time without similar past situations?

Helmholtz's suggested we use the principle of maximum likelihood.

We make a tally of all the similar past experiences to predict what parts matter.

But:

How do we know which tally to use?

When do we take the context into account?

Do we need all the situations aspects?

How do we interpret the surroundings?

Where did the interpretation come from? Another tally?

The questions can continue…

One that sticks out to me.

“How do you know what's likely if you don't already know what's likely?”

-Introduction to Ecological Psychology pg 19-20

Dennet referred to this as the loan of intelligence.

The central executive requires lots of information to get started, with no clear answer to how it gets it.

Robots are programmed.

Were we?

Is the matrix real...?

Something else to consider.

If the central executive uses the presumed bad senses for information, how does it get accurate feedback to update our programs (cues and rules)?

So what?

Many solutions, including Helmholtz's rely on the 'high cognitive reasoning' humans have to create representations.

But as discussed in the book, most if not all organisms can perform everyday behaviours.

Obtaining food.

Acquiring shelter.

Locating mates.

So:

“Is it possible to create a perceptual system that doesn't require interpretation?”

Following these 8 assumptions, we are left in a bit of a pickle.

The world actually exists.

We are born with no knowledge and gain all knowledge through our senses.

Our senses (somehow) inform us about the world.

All causality must be local.

Contact with the world is mediated by a copy.

The copy delivered to the brain is bad and needs to be fixed.

Unconscious inferences is used to fix the bad copy - learned cues and rules are unconsciously applied to create a mental representation of the world.

Once the copy is fixed, the representation of the world is your experience of the world.

But we can't fix the bad copy without prior information or accurate feedback, so we are left with some unsolvable mysteries:

How does the central executive know the stimulation came from out there in the world if it uses our senses as a source?

Why would the central executive question the accuracy of our senses if it knows no different?

What tells the central executive the world is actually 3-dimensional if we see in 2 dimensions?

How do we gain knowledge about something for the first time without similar past situations?

If the central executive uses the presumed bad senses for information, how does it get accurate feedback to update our programs (cues and rules)?

If you are curious about where we potentially went wrong, subscribe for the next article.

PS: I would highly recommend purchasing a copy of the book if this interests you!